How to revive a tired network

Herminia Ibarra

3 February 2015

On a scale of one to five, how important is having a good network to your ability to accomplish your goals? When I ask my executive students this question, most of them answer in the fours and fives. Even the most naive of them agree that, like it or not, relationships hold the key to both their current capacity and future success.

What can a network do for you? It can keep you informed. Teach you new things. Make you more innovative. Give you a sounding board to flesh out your ideas. Help you get things done when you are in a hurry and you need a favor. The list goes on.

When it comes to stepping up to leadership, your network is a tool for identifying new strategic opportunities and attracting the best people to them. It’s the channel through which you sell your initiatives to the people you depend on for cooperation and support. It’s what you rely on to win over the skeptics. It protects you from being clueless about the political dynamics that so often kill good ideas. Your relationships are also the best way to change with your environment and industry, even if your formal role or assignment has not changed. Without a good network, you will also limit your own imagination about your own career prospects. Your network is also what puts you on the radar screen of people who control your next job or assignment and who form their opinion of your potential partly on who knows you and what they say about you.

But just because you know that a network is important to your success, it doesn’t mean you are devoting sufficient time and energy to making it useful and strong. In fact, few of us do. I know because I ask a second question: on a scale of one to five, how would you rate the quality of your current network?

My guess is that your second number is lower than your first. On average, my executive students answer this question in the twos and threes. Most admit that even by their own standards, their networks of connections leave much to be desired.

The good news is that you can change that. By managing the three key properties of networks that either propel you forward or hold you back — breadth, connectivity, and dynamism — you can develop a stronger network and use it as an essential leadership tool. This article will show you how to reinvent your network, by managing these three critical dimensions.

To start, assess the network you have today. Panel 1 A network audit lets you conduct a quick-and-dirty audit of your present network. The questions represent a short version of the survey I use with my students.

As you’ll see, there are three basic sources of connective advantage that you will need to build into your network. As you read the next section, you may want to return to this network audit to assess if these properties of networks are working for you or against you.

The BCDs (breadth, connectivity and dynamism) of networking advantage

Your network’s strategic advantage and, therefore, the extent to which it helps you step up to leadership, depends on three qualities:

Breadth: strong relationships with a diverse range of contacts.

Connectivity: the capacity to link or bridge across people and groups that wouldn’t otherwise connect.

Dynamism: a dynamic set of extended ties that evolves as you evolve.

I call these three qualities the BCDs of network advantage, or A=B+C+D.

Breadth: how diverse is your network?

One of the first things that my students notice when they audit their networks is that the network formed by the people they talk to about important work matters is much more internally focused than it should be. As these managers start to concern themselves with broad strategic issues and organizational change processes, lateral relationships with people outside their immediate area become even more critical to the managers’ ability to get things done. And in a connected world, building stronger external networks to tap into the best sources of insight into environmental trends is also part and parcel of the leadership role.

Data compiled from the network surveys I give my participants shows that we are still not using networks to our best advantage. We build networks that are heavily skewed toward our own functional, business, or geographical group and fail to elicit or value the input and perspectives of peers from different functional or support groups. Moreover, we are still relying on networks that are mostly internal to our company, in a world where the rate of change outside is considerable.

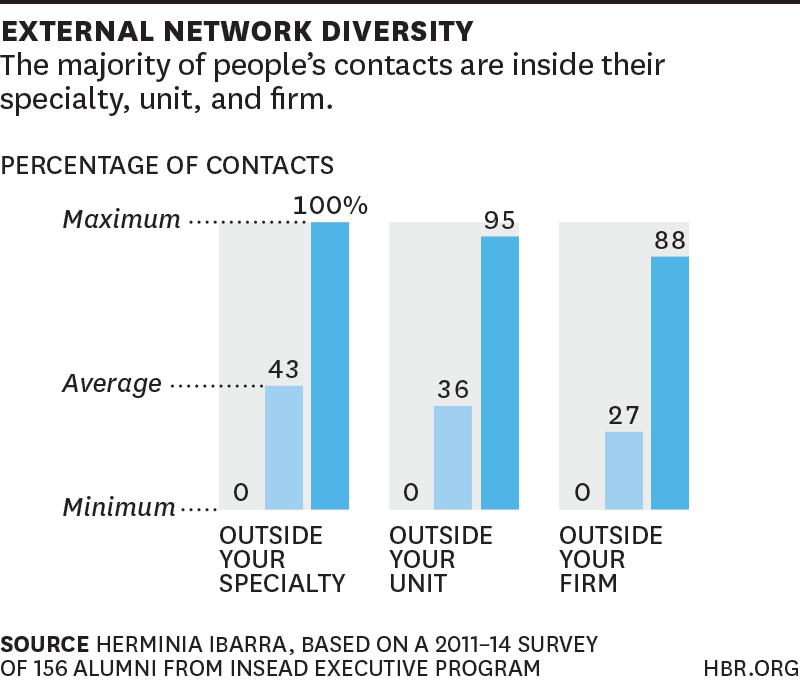

As the descriptive statistics in the below figure External network diversity show, the majority of my students’ contacts are inside their specialty, unit, and firm. On average, less than 43% of the people the executive students were discussing key issues with were located outside their unit or specialty; even fewer, only a quarter, were external to their company. But averages can be deceiving: the range of values shows that some of the managers in the survey have no contacts at all outside their specialty, unit, or firm.

You can also overdo diversity: the ranges also show that some of the executives have heavily external networks: up to 100% and 95% outside their specialties and units, respectively, and 88% outside their companies. That’s fine if an executive is looking to move elsewhere, as some of my participants were. But an exclusively outside network is not as useful if you are trying to bring an outside approach into your own company. You can’t bridge the outside to the inside if you haven’t established strong relationships on the inside.

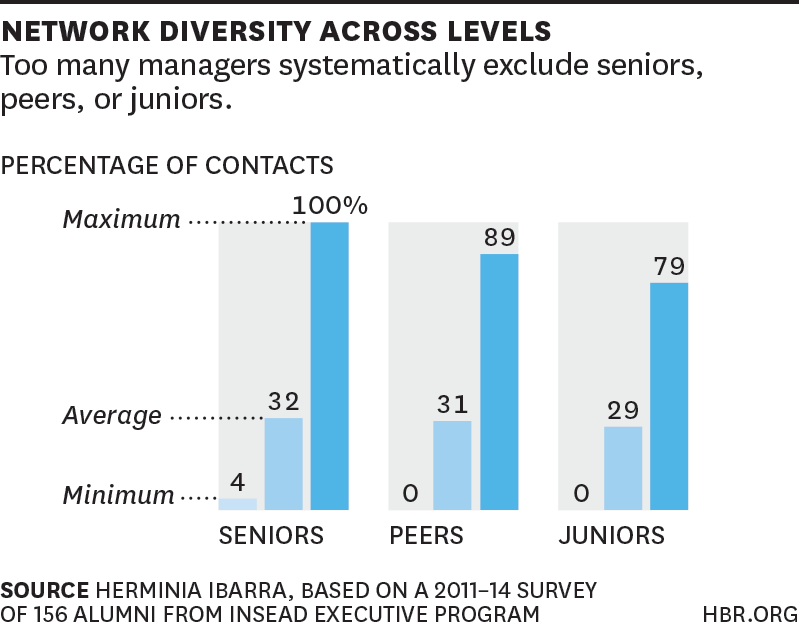

Another common network blind spot consists of undervaluing the potential contributions of junior people. Managers striving to make their way up the leadership pipeline tend to manage up, forgetting that their connection to the layers below is often what makes them invaluable to seniors whose sponsorship they hope to attract. One manager explained it to me this way: “I would perhaps have been able to add even more value to my superiors if I had retained my links with more junior people. For example, recently we were in a meeting discussing the results of a global people survey. I was listening to all their comments, and I said, ‘You guys are looking at this from the perspective of very senior people; be careful about how you are interpreting the results. [People at a lower level] are saying something completely different.’ I knew that because I had been spending time with them.” Given a choice between a network heavily skewed to the power players in your firm and a good mix of diverse contacts, which would you choose? Research shows that you are better off with the latter. This is because networks run on the principle of reciprocity. The value of diverse relationships lies not only in what your contacts can do for you, but also on what you can do for them. Your senior leaders don’t need you to connect them with other seniors; they already know each other. Top management needs you to bring them the fresh ideas, insights, and best practices that you can only get elsewhere, outside, across, and below. As the figure Network diversity across levels shows, too many managers lack the 360-degree perspective you can only get from cultivating relationships with a mix of peers, juniors and seniors. Although the averages suggest that people focus their networking on approximately one-third of each group, the range of the scores shows that too many managers systematically exclude one of these groups. Panel 2 below Why we need fresh blood explains how diversity on any team often produces the best results.

On making a list of their relationships, even highly experienced leaders find that they’ve failed to network with people who are different from them or to build bridges across and outside their organization’s lines. Check the diversity of your network by returning to the list you made in your network audit. To what extent are your relationships externally facing? Have you included a good mix of people occupying different levels and functions?

How connective is your network?

So far we’ve looked at who the people are in your network and how you are connected to these people. Now we’ll turn to how your contacts are connected and what that means for you.

The connectivity of your network is the basis for the famous six degrees of separation principle — the idea that we are rarely ever more than six links removed from anyone else in world through the friends of our friends — discovered by Harvard psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s. As any LinkedIn user knows, the fewer degrees of separation between any two people in a network, the easier it is to access the resources you need.

In the original study, Milgram gave a bunch of people in Nebraska a letter destined for a stockbroker in Massachusetts —a man they didn’t know. Their job was to get the letter to him by sending it to someone they did know, who might then send it to someone else, ultimately reaching the stockbroker. Milgram found that it never took more than six links (thus the six-degrees concept) to reach the stockbroker, for those letters that actually arrived. But many of the letters never got there, because the first degree — the people his participants knew directly and contacted first — didn’t have networks that reached outside their local environment. So, many of the letters never got out of Nebraska. They only circulated inside the same circle of people who all knew each other.

Something similar happens when you fall prey to the biggest trap in networking: everyone you know knows the same people you do, and the flow of information gets stuck in the same office, in the same industry, in the same neighborhood. Sociologists use the term density to describe this property of networks: it quantifies the percentage of people who know each other in a network. Density is an imperfect measure, but it is a quick way to check how much six-degree potential you have in your network.

2. Why we need fresh blood

Stefan Wuchty, Benjamin Jones, and Brian Uzzi, a multidisciplinary team of researchers, decided to use big data to learn what distinguished ideas that had impact from those that didn’t. In a massive study of the 20 million academic articles and two million patents cited over the past 50 years, which Wuchty and his colleagues published in the prestigious journal Science, they found that the difference lies in the kinds of networks that produce the ideas (footnote a).

The study showed that the days of the solitary genius or lone inventor — think Newton or Einstein — are over. Creative and scientific work has migrated to teams and, more recently, to large, distributed teams like the hundreds of scientists that worked on the human genome project.

But being part of a team wasn’t enough for high impact, as measured by article and patent citations. The really great ideas were much more likely to come from cross-institutional collaborations rather than from teams from the same university, lab, or research center. Not only that, but the most successful teams mixed things up. They avoided the trap of always working with the same people, and successful groups brought to the team both newcomers and people who had never collaborated before.

Uzzi and another colleague, Jarrett Spiro, also discovered that this pattern held across sectors as disparate as the Broadway musical industry and biotechnology (footnote b). Between 1920 and 1930, for example, 87% of Broadway shows flopped despite being attached to big names like Rogers & Hammerstein, or Gilbert & Sullivan. When well-known composers like these continued to work together without the benefit of fresh blood, their creations suffered, critically and financially. The most successful plays, instead, resulted from collaborations among diverse players. Leonard Bernstein’s West Side Story, for example, which went on to become a mega-hit, featured newcomer Stephen Sondheim and other new collaborators.

(a) Stefan Wuchty, Benjamin F. Jones & Brian Uzzi, ‘The Increasing Dominance of Teams in Production of Knowledge’, Science 316, no. 5827 (2007): 1036–1039.

(b) Brian Uzzi & Jarrett Spiro, ‘Collaboration and Creativity: The Small World Problem’, American Journal of Sociology 111, no. 2 (2005): 447–504.

If you are like many of the successful executives I teach, chances are that your density score is higher than it should be. When I conduct this exercise in class, the average density hovers above 50%, although it is significantly lower for professionals who work mostly with outside clients such as consultants, investment bankers, lawyers, headhunters, and auditors and for people who go back to school to orchestrate a career change. The range of scores always extends to 100%: when nearly everyone with whom you discuss important work issues knows each other, you have an inbred network. There’s no other way to put it.

To understand the problems of having an inbred network, let’s look at the effects of network density in a completely different context: the so-called obesity epidemic. Two previously unknown university professors, Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler, became overnight celebrities when they showed that being overweight can be contagious.

Christakis and Fowler analyzed the health records and social relationships of 12,000 Framingham, Massachusetts, residents from 1948 to the present. Using advanced visualization techniques and careful statistical controls, they showed that overweight people tend to hang together socially, while thin people tend to be friends with other thin people. But this is not a mere correlation showing that birds of a feather flock together: being connected socially to people who are overweight, even indirectly, seems to make a person overweight. The researchers concluded that thin and overweight people tend to live their lives within different and unconnected social clusters —‘microclimates’, so to speak — within which different social norms about what is normal and desirable have developed. Political views also hang by cluster. Tightly connected members apparently had no external perspective on the world beyond their immediate group.

At work, when we surround ourselves with people like us and with whom we’ve worked before, the network creates an echo chamber in which no new information circulates because everyone has the same sources. That’s how groups become mired in consensus, and after a while, everyone thinks and acts alike. Panel 3 below The innovators’ network dilemma presents convincing data that bears out this observation.

This state of affairs also limits significantly how valuable you are to your network, since you bring nothing unique that the network members can’t get elsewhere. Your comparative advantage— how you differentiate yourself from others who are as smart, hardworking, or expert as you are—depends on your capacity to connect people, ideas, and resources that wouldn’t normally bump into one another.

Some research suggests that there’s an optimum level of density, about 40%. But of course, that depends a lot on what a person’s job is. When your network gets too sparse, you lose connectivity. You are a ‘visitor’ to many networks but a ‘citizen’ of none. You may have access to lots of ideas and people, but you can’t put them to use inside your organization (or any other group to which you belong), because you lack inside information about how to pitch your ideas, who might be opposed to them, and how to win people over — all critical parts of leading change.

Too sparse a network, and you might also lack credibility and visibility with important gatekeepers, who might not know you well but who implicitly evaluate you on the basis of who you know that they also know (the principle on which professional networks like LinkedIn work). This is often a problem when you are the minority in a group. People are apt to have relationships with people like them, so minorities and majorities and professional men and women are unlikely to have highly overlapping networks. In a study of boards of directors, for example, James Westphal found that minority directors tend to be more influential if they have direct or indirect social network ties to majority directors through common memberships on other boards. These overlapping networks serve as a form of social verification and increase the likelihood that the minority’s ideas will be heard.

In sum, as Malcolm Gladwell illustrated in his book The Tipping Point, networks run on ‘connectors’, people who are linked to almost everyone else in a few steps and who connect the rest of us to the world. Connectors can see a need in one place and a solution in another, a vacancy in one area and a talented person in another, a discovery from a different discipline and a problem in their own, and so on, because they’re just one or two ‘chain lengths’ away from the issues. That is, you can reach connectors through someone you already know or through someone who knows someone whom you already know.

3. The innovators’ network dilemma

A study by University of Chicago sociologist Ron Burt demonstrates the cost of inbred networks.

When Burt studied managers in the supply chain of Raytheon, the large electronics company and military contractor based in Waltham, Massachusetts, he discovered that the company had no trouble coming up with good ideas but considerable difficulty turning these ideas into reality.

Burt asked the managers to write down their best ideas about how to improve business operations, and then he asked two executives at the company to rate the quality of these ideas. He then mapped out the network of who consulted with whom. Burt was looking for what he calls ‘structural holes’, gaps between cohesive groups of people with dense patterns of informal communication among them and few ties outside their circle.

His many years of research have shown that people whose networks span these holes reap the greatest network benefits. These people see more and know more. They have more power because other people have to go through them to connect outside their group.

Not surprisingly, the highest-ranked ideas came from managers who had contacts outside their immediate work group. Most managers, however, overwhelmingly turned to colleagues already close in their informal discussion network to bounce ideas off (think ‘inbred circle’). The result was that their ideas were not developed (footnote a).

(a) Ronald S. Burt, ‘Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition’ (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995); Ronald S. Burt, ‘Structural Holes and Good Ideas’, American Journal of Sociology 110, no. 2 (2004): 349–399. See also Gautam Ahuja, ‘Collaboration Networks, Structural Holes, and Innovation: A Longitudinal Study’, Administrative Science Quarterly 45, no. 3 (2000): 425–455.

How dynamic is your network?

One of the biggest drawbacks of a poorly managed network is that it quickly becomes a historical artifact, the residue of manager’s past rather than a tool to move into the future. We change jobs, firms, and even countries, but our networks lag behind our new responsibilities and aspirations and therefore pigeonhole us just when we need a fresh perspective or seek to move into something different. Joel Podolny, former head of Apple’s human resources, calls this tendency of our networks to evolve more slowly than our jobs ‘network lag’. We’re exceptionally slow to build relationships that allow us to perform in a new position or prepare us for future roles.

When asked about the strengths of their network, most people think first about the quality of their relationships. They value most their strong ties, because trust is essential when it comes to getting things done, and we trust most the people we know best. But as we have seen, the people we know best are not necessarily those who can prepare us for stepping up. To make your networks future facing, you’ll need to build and value your weak ties — that is, the people and groups that are currently on the periphery of your network, those you don’t see very often or don’t know so well (see panel 4 below Making your network future facing). What’s important about these contacts is not the quality of your relationship with them (just yet), but the fact that they come from outside your current world. These contacts tend to be several levels removed from you or circulate in different circles.

That makes reaching out harder. Getting to know your weak ties or getting to know them better usually requires an explicit plan and strategy — these relationships will never evolve naturally, because you have no common context in which to develop them. Nevertheless, these are the ties from which you stand to gain the greatest outsight.

Another problem with relying exclusively on your strong-tie network is that it limits your capacity to rethink yourself. In my study of 39 mid-career managers and professionals considering major career changes, I observed directly how much their old networks can ‘bind and blind’ them. All of them were told by a friend, family member, or close coworker that they must be out of their minds for thinking about quitting their jobs or leaving their organizations. The people close to you may mean well, but they are often not helpful when you are trying to stretch yourself. Despite their good intentions, they hold restrictive views of who you are and what you can do. So, they are the people most likely to reinforce — or even desperately try to preserve — the old identity you are trying to shed.

4. Making your network future facing

A financial services firm executive, Pam, realized that she was unprepared when her job became more externally facing. “I was fairly well networked internally and within my region,” she told me, “but I had no external network or external points of connectivity, and I don’t think I understood the value of those external points.” Never one to give much thought to whom she knew, she realized the time had come to build a new network systematically. Here are the steps she followed:

- Identify 20 to 25 key stakeholders you wish to stay connected to in a meaningful way.

- Assign these contacts into key categories:

– Most-senior clients

– Most-senior people in your company

– Most-senior hedge fund people and competitors

– Most-senior service providers (e.g., lawyers, accountants)

– Most-senior women in financial services. - For each category, select the three to five people you want to stay connected to.

- Decide how frequently you will reach out to each contact.

These three sources of network advantage — the diversity of your contacts, your connectivity within the network, and your network’s dynamism — are obviously interrelated. Without these advantages, you never meet new people and the circle closes; over time, you lose relevance.

Return to the network audit that you completed, and check what you listed as the strengths and weaknesses of your current network. Which of the following weaknesses that we discussed above are true for you?

- Birds of a feather: your contacts are too homogeneous, all like you.

- Network lag: your network is about your past, not your future.

- Echo chamber: your contacts are all internal; they all know each other.

- Pigeonholing: your contacts can’t see you doing something different.

5. Getting started: experiments with your network

In the next three days, talk to three people outside your business unit or company; learn what they do, how it helps the company, and how it may apply to your work.

In the next three weeks, reconnect with people outside the company who may shed useful light on your work, industry, or career. Have lunch.

Make a list of five senior people you need to get to know better. Figure out ways to strengthen your relationship over the next three months.

Summary

✓ As you embark on the transition to leadership, networking outside your organization, team, and close connections becomes a vital lifeline to who and what you might become.

✓ The only way to realize that networking is one of the most important requirements of a leadership role is to act.

✓ If you leave things to chance and natural chemistry, then your network will be too inward-facing and not diverse enough.

✓ You need operational, personal, and strategic networks to get things done, to develop personally and professionally, and to step up to leadership. Although most good managers have good operational networks, their personal networks are disconnected from their leadership work, and their strategic networks are non-existent or under-utilized.

✓ Network advantage is a function of your BCDs: the breadth of your contacts, the connectivity of your networks, and your network’s dynamism.

✓ Enhance or rebuild your strategic network from the periphery of your current network outward as a first step toward increasing your outsight on your self: seek outside expertise. Elicit input and perspectives of peers from different functional or support groups.

6. Practical steps to expand your network

- Spend time at a start-up within your business sector. Consider why incumbents rarely lead the way in new products and services.

- Attend a conference you have never before attended. Meet at least three new people. Follow up with them afterward.

- Start a LinkedIn or Facebook group. Be the connector for this group of people.

- Spend a day with a millennial in your company. Learn more about how she uses social media.

- Get in touch with a venture capitalist. Find out how he thinks about leadership and innovation.

- Teach a course at a university or local college. Learn from your students.

- Be a guest speaker at a local or national event. Use it to build or strengthen your brand around a particular area of expertise.

- Go to lunch with a peer from a competing company. Learn more about your market value.

- Start a blog. Find out who reads it.

- Take advantage of your next business trip to connect with someone you’ve lost track of. Have this person help you connect with someone new.

Read the original article on Harvard Business Review.